I just finished reading (and re-reading) Pale Fire. Needless to say, I am amazed. This book is a beautifully intricate puzzle crafted for careful readers, which rewards them with ample discovery.

Although I might do a full review at a later point, I wanted to jot down some of the things/lines from the book which caught my eye, both at second and first readings; I will probably continuously update this document to reflect new things I’ve noticed or found. A lot of what I’m writing down I got from doing a bit of research on Google, but I think I can proudly say that I did manage to solve quite a few of Nabokov’s riddles.

Obviously, spoilers ahead.

I think everyone knows about the Vseslav Botkin theory, so I won’t write too much about that - this is more a set of small remarks, or little gems I found. I did manage to find almost all of these myself, so I am quite proud of that.

Wordplay, allusions, small clues

Note that Nabokov, in beautiful style, gives us the solution to the puzzle in the Foreword:

“…in my early boyhood I once watched across the tea table in my uncle’s castle a conjurer…”

Later, another hint straight out of the Foreword:

“Let me state that without my notes Shade’s text simply has no human reality…”

Line 241:

“That Englishman in Nice,

A proud and happy linguist: je nourris

Les pauvres cigales - meaning that he

Fed the poor sea gulls!

Lafontaine was wrong:

Dead is the mandible, alive the song.”

First of all, cigales is obviously not a seagull in French; it’s a cicada.

Secondly, this is also quite a clear allusion to Lafontaine’s story La Cigale et la Fourmi. This is an interesting reference, since this story was known to have no clear message, and therefore an ambiguous ending; in summary, the story is about a cicada that comes to an ant, asking it for food. When the ant asks why the cicada doesn’t have any food, it replies saying that it’s because it spends all day singing. The ant mocks her and tells her to then start dancing, and doesn’t share any of its flies.

This little fable in itself has been analysed to death in many different contexts (some going as far as saying that this represents a bourgeois ant and a proletarian cicada), but I think here the allusion is quite straightforward: dead is the mandible (the ant), alive the song (the cicada). Shade is known for his affection towards the natural world; does he identify himself with the singing cicada, a carefree poet who is more alive than any of the workers (ants) around him?

Line 312:

“My gentle girl appeared as Mother Time…”

This is already mentioned by Kinbote, but there is a dual to this phrase, in line 475:

“A watchman, Father Time”

Line 413:

“A nymph came pirouetting, under white

Rotating petals, in a vernal rite

To kneel before an altar in a wood

Where various articles of toilet stood.”

Throughout the commentary and Pale Fire itself, we often see Alexander Pope regularly appearing as one of Shade’s favourite poets. These lines are an allusion to one of Pope’s works, The Rape of the Lock:

“And now, unveil'd, the Toilet stands display'd,

Each silver Vase in mystic order laid.

First, rob'd in white, the Nymph intent adores,

With head uncover'd, the Cosmetic pow'rs.

A heav'nly image in the glass appears,

To that she bends, to that her eyes she rears;

Th' inferior Priestess, at her altar's side,

Trembling begins the sacred rites of Pride.”

In these lines, Pope is making fun of his main character, Belinda; she doesn’t just get ready to go out, her Toilet is exquisitely arranged for nymphs. In a similar way, is Shade pitying his daughter’s constant pathetic effort to look beautiful? I’m not sure, since this wouldn’t really be in line with Shade’s characterisation in general. But for whatever reason, a clear parallel is drawn between Hazel Shade and Belinda’s preparation.

Lines 440-442:

“The man in the old blazer, crumbing bread,

The crowding gulls insufferably loud,

And one dark pigeon waddling in the crowd.”

Kinbote mentions in his commentary to line 803 the korona/vorona/korova wordplay in Russian (crown, crow, cow). Similarly, above we get a play between crowds, a crow (dark pigeon?), and back to crowd. Is the man in the blazer the same person who is feeding the cigales?

Line 501 and Kinbote’s commentary:

“L’if, lifeless tree! Your great Maybe, Rabelais:

The grand potato.”

There’s two things happening here.

Firstly, as Kinbote correctly comments, this is the word for yew in French. However, he then makes two interesting remarks:

“It is also curious that the Zemblan word for the weeping willow is also ‘if’ (the yew is tas).”

In Russian, the word for weeping willow is iva, and word for yew is tis, not tas. Is this an allusion to Kinbote’s true nature? He gets confused as to what language is truly his, giving Zemblan a general air of Russian.

Another interesting thing to note here is that yew trees are poisonous, and ingesting even a small bit of one can result in death. Specifically, though, the yew tree is historically with suicide, and there are quite a few famous cases of someone eating a yew branch to kill themselves. Most notably though (from Wikipedia):

“In the ancient Celtic world, the yew tree (*eburos) had extraordinary importance; a passage by Caesar narrates that Cativolcus, chief of the Eburones, poisoned himself with yew rather than submit to Rome (Gallic Wars 6: 31). Similarly, Florus notes that when the Cantabrians were under siege by the legate Gaius Furnius in 22 BC, most of them took their lives either by sword, fire, or a poison extracted ex arboribus taxeis, that is, from the yew tree (2: 33, 50–51). In a similar way, Orosius notes that when the Astures were besieged at Mons Medullius, they preferred to die by their own swords or by yew poison rather than surrender (6, 21, 1).”

Why would Botkin single out a single word from the line? I think this lends a lot of credibility to the suicide theory.

Line 679 and Kinbote’s comment:

“It was a year of Tempests: Hurricane

Lolita swept from Florida to Maine.”

And Kinbote’s funny response:

“Major hurricanes are given feminine names in America. The feminine gender is suggested not so much by the sex of furies and harridans as by a general professional application. Thus any machine is a she to its fond user, and any fire (even a ‘pale’ one!) is she to the fireman, as water is she to the passionate plumber. Why our poet chose to give his 1958 hurricane a little-used Spanish name (sometimes given to parrots), instead of Linda or Lois, is not clear.”

Line 893:

“And with his toe renewing tap-warmth, he’d

Sit like a king there, and like Marat bleed.”

Shade compares himself to Marat? Why?

Marat was a martyr. I think reading this line in a specific context could give some credibility to the “Shade invented everything” hypothesis, including the invention of his death and then the alter ego of Kinbote (or Botkin).

Now, one of the most mysterious lines, line 936:

“…and now I plough

Old Zembla’s fields…

…

Man’s life as commentary to abstruse

Unfinished poem. Note for further use.”

Shade directly mentions Zembla. I doubt that Shade would have done this out of some kind of pity towards Botkin, since he is not mentioned a single time in the entire poem. I think these few lines, again, give some strong credibility to the “Shade is Botkin” theory. Note the final two lines: note for further use. Is Shade writing a note to his future self (Botkin) as to what to do?

I now move on to things I noticed from the commentary itself; I definitely missed a million things in the poem, but so far I’ve only carefully reread the index and the comments.

Lines 1-4:

“My knowledge of garden aves was limited to those of northern Europe but a young New Wye gardener, in who I was interested (see note to line 998)…”

Kinbote clearly alludes to his northern home, Russia. This is also the first hint of Kinbote’s homosexuality. If we follow the track to line 998, we find:

“…he was a strong strapping fellow, and I hugely enjoyed the aesthetic pleasure of watching him buoyantly struggle with earth and turf or delicately manipulate bulbs, or lay out the flagged path which may or may not be a nice surprise for my landlord, when he safely returns from England (where I hope no bloodthirsty maniacs are stalking him!)”

Not only is the homosexuality theme developed, but we also get a strange clue to the cause of Shade’s death; again, from the very first reference of the first comment to the first lines of the poem. Nabokov hid the solution to his puzzle in the very first lines.

“Line 12: that crystal land

“Perhaps an allusion to Zembla, my dear country.”

Kinbote then mentions something out of a draft:

“Ah, I must not forget to say something

That my friend told me of a certain king.”

If we then flip through to the comment of line 550, Kinbote sheepishly says:

“I wish to say something about an earlier note (to line 12). Conscience and scholarship have debated the question, and I now think that the two lines given in that note are distorted and tainted by wistful thinking. It is the only time in the course of the writing of these difficult comments, that I have tarried, in my distress and disappointment, on the brink of falsification. I must ask the reader to ignore these two lines…I have no time for such stupidities.”

Again, one of the first allusions to Zembla is quickly dispelled by a later note. Once again, solutions are right in front of our eyes the whole time, but we don’t notice them until a rereading.

It’s also worth noting that in this commentary, Kinbote explicitly mentions the dates of the King’s reign (1936-1958). The foreword to Pale Fire is written in October of 1959. Why does the King’s reign end in 1958, then? Is this Kinbote planning his suicide?

In this same commentary, there are quite a few more interesting lines:

“The poor were getting a little richer, and the rich a little poorer (in accordance with what may be known some day as Kinbote’s Law)…when the rowans hung coral-heavy, and the puddles tinkled with Muscovy glass…Everybody, in a word, was content - even the political mischiefmakers who were contentedly making mischief paid bz a contented Sosed (Zembla’s gigantic neighbour)…”

Kinbote directly alludes to himself as being somehow related to the creation of Zembla’s laws. Muscovy glass refers to Russian glass, and sosed means neighbour in Russian. We are given lots of clues on Kinbote’s origin - it’s not hard to guess that he is, in fact, Russian.

Continuing in the same passage:

“…discuss the Zemblan variants, collected in 1798 by Hodinski, of the Kongsskugg-sio (The Royal Mirror)…I who have not shaved now for a year, resemble my disguised king.”

Hodinski could be alluding to a number of different people, I’m not sure who exactly, but I saw a few sources to this potentially being Khlebnikov. The Konungs skuggsjá (old Norse for King’s Mirror) is an ancient Norwegian epic. Botkin looks into a mirror and sees himself unshaven - he looks like the disguised king.

“Line 27: Sherlock Holmes

…our poet simply made up this Case of the Reversed Footprints.”

This is false. After Sherlock Holmes fights Moriarty, he must explain to Watson the trail of footprints awkwardly leading backwards. Not only does this show Kinbote’s unreliability, but also alludes to a story in which Sherlock magically escapes death. Kinbote dismisses this as “made up”. He is accepting his fate.

In the commentary to lines 47-48, Kinbote gives us one of the biggest clues in the book, and also alludes to the strangely vague nature of a lot of his memories:

“The charming, charmingly vague lady (see note to line 691)…All the layman could glean for instruction and entertainment was a Morocco-bound album in which the judge had lovingly pasted the life histories and pictures of people he had sent to prison or condemned to death…the close-set merciless eyes of a homicidal maniac (somewhat resembling, I admit, the late Jacques d’Argus)…”

So we have come to understand that Gradus is someone who was sentenced by Goldsworth. This person is then the one who shows up at his house and shoots Shade.

If we look at who the vague lady is in comments to 691, this woman is revealed to be Sylvia, who secured the rental house for Kinbote; the commentary to 691 is also, I think, the first time Kinbote uses the pronoun “I” when referring to the King of Zembla. He describes Sylvia as:

“Good old Sylvia! She had in common with Fleur de Fyler a vagueness of manner…volubility remind one of a slow-speaking ventriloquist who is interrupted by his garrulous doll. Changeless Sylvia!”

So, Sylvia has remained unchanged forever, and her defining feature is that she is vague and reminds one of a ventriloquist? I think there is also something interesting to be traced with the character of Fleur, but I have not yet noticed her (and Odon’s) relevance. At a basic level, one notices that her name (Fleur Defyler) means one who defiles flowers.

From the same passage (comment to lines 47-48), there’s also a potential motivation for the killer’s (Gradus’) actions:

“…terrifying shadows that Judge Goldsworth’s gown threw across the underworld…”

Continuing, a nice little easter egg:

“Windows, as well known, have been the solace of first-person literature throughout the ages. But this observer never could emulate in sheer luck the eavesdropping Hero of Our Time or the omnipresent one of Time Lost…”

Despite being a pretty much perfect novel, a large part of Pechorin’s plot in Hero of Our Time revolves around a chance eavesdropping in bushes or through windows - if I remember, this is especially true in the second and final chapters of the book. I haven’t read Proust.

One of my favourite small passages:

“…Professor C’s ultramodern villa from whose terrace one can glimpse to the south the larger and sadder of the three conjoined lakes called Omega, Ozero, and Zero (Indian names garbled by early settlers in such a way as to accommodate specious derivations and commonplace allusions.)”

The Russian word for lake is, of course, ozero. I think this is a beautiful little gem - making fun of the allusions as soon as one catches them.

In the commentary to line 49, there is also a very satisfying passage, to which readers are given a direct hint:

“Disa…copied out in her album a quatrain from John Shade’s collection of short poems Hebe’s Cup, which I cannot refrain from quoting here (from a letter I received on 6 April, 1959, from southern France):

THE SACRED TREE

The ginkgo leaf, in golden hue, when shed,

A muscat grape,

Is an old-fashioned butterfly, ill-spread,

In shape.

When the new Episcopal church in New Wye was built, the bulldozers spared an arc of those sacred trees planted by a landscaper of genius (Repburg) at the end of the so-called Shakespeare avenue, on the campus. I do not know if it is relevant or not but there is a cat-and-mouse game in the second line, and ‘tree’ in Zemblan is grados.”

A few things from this:

Disa is both the name of an orchid and the name of a butterfly, Erebia Disa.

Who could have Kinbote received this letter from? This is not clear to me.

Obviously, allusions in bold.

Commentary to line 62:

“I cannot describe the depths of my loneliness and distress…back to Zembla, Rodnaya Zembla…At times I thought that only by self destruction could I hope to cheat the relentlessly advancing assassins…

Balthasar, Prince of Loam, as I dubbed him, who with elemental regularity fell asleep at nine and by six in the morning was planting heliotropes (Heliotropium turgenevi). This is the flower whose door evokes with timeless intensity the dusk, and the garden bench, and a house of painted wood in a distant northern land.”

Zembla (I would spell it Zemlya) means land in Russian, and Rodnaya Zembla means “native land”.

Balthasar is one of the Magi. Why would Kinbote dub him as such?

This is actually a Shakespeare reference: Balthasar is Romeo’s servant. Hamlet repeats “loam” twice:

HAMLET.

To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bung-hole?

HORATIO.

'Twere to consider too curiously to consider so.

HAMLET.

No, faith, not a jot; but to follow him thither with modesty enough, and likelihood to lead it: as thus: Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth into dust; the dust is earth; of earth we make loam; and why of that loam whereto he was converted might they not stop a beer-barrel?

Heliotropium turgenevi is, of course, not a real name: this is a reference to Turgenev’s favourite flowers of heliotropes, which actually also make an appearance in chapter 3 of The Gift.

In commentary to line 71, Alfin (the king’s supposed father) is described as Alfin the Vague. This is already the second character from the King’s past whose main defining feature is that they are vague.

There is also a mention of the islands of Nitra and Indra. I don’t doubt Nabokov knew who Indra was. Why did he choose these two names? Are these anagrams? I’m not sure.

Perhaps a nostalgic easter egg from Nabokov:

“King Alfin was in the act of trying solo a tricky vertical loop that Prince Andrey Kachurin, the famous Russian stunner and War One hero, had shown him in Gatchina.”

There are many parallels between the biography of Botkin/Kinbote and Nabokov, but this is a particularly striking one: Nabokov’s family estate was around the town of Gatchina, which today is in the Leningrad Oblast. I caught this because I also used to spend many summers in Gatchina.

Kinbote also mentions “excruciating headaches”. I’m not sure how this is related, but Gradus also suffers from migraines.

In the same commentary is a reference to “the Elder Edda”; the Poetic Edda is an ancient Norse text.

From commentary to line 130:

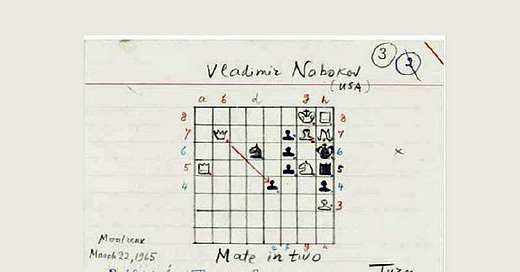

“In simple words I described the curious situation in which the King found himself during the first moths of the rebellion. He had the amusing feeling of his being the only black piece in what a composer of chess problems might term a king-in-the-corner waiter of the solus rex type.”

This is a really interesting passage, since Nabokov actually sets up, before us, a chess problem; namely, since it’s a ‘waiter’, how does the king escape? He must wait for the opposing side to move first. This idea can actually be developed a lot further, since it’s possible that this is the first clue in solving the Crown Jewels problem, disguised as a chess problem.

Secondly, solus rex is mentioned twice in the book. Apart from the obvious translation meaning “lone king”, Solus Rex was also the name of Nabokov’s last unfinished work in Russian. In the same passage:

“…harmless conscripts from Thule…”

The first chapter of what was supposed to be Solus Rex ended up becoming Nabokov’s last short story in Russian, Ultima Thule. Thule means island.

Line 137: lemniscate

This is very interesting; a lemniscate is the symbol of infinity. I’ll come back to this in the context of the poem.

Line 143: a clockwork toy

Remember that King Charles claims to have found clockwork toys in his own castle’s basement; in this commentary, Kinbote finds a clockwork toy inside Shade’s basement.

“The boy was a little Negro of painted tin with a keyhole in his side and no breadth to speak of, just consisting of two more or less fused profiles, and his wheelbarrow was now all bent and broken. He said, brushing the dust off his sleeves, that he kept it as a kind of memento mori - he had a strange fainting fit one day in his childhood while playing with that toy…I have the key.”

Not only is this the exact image of how Shade dies (Botkin’s black gardener is pushing a wheelbarrow up the street when Gradus shoots), but there is also mention of a key. What key? Is this the same key which was relevant to open the underground tunnel of the King’s castle? I’m not sure. So this is both foreshadowing and a clue.

Commentary to line 171:

“..But Gradus should not kill kings. Vinogradus should never, never provoke God. Leningrad’s should not aim his peashooter at people even in dreams…”

Does this give us a glimpse into Kinbote’s past? He is harbouring deep resentment against a revolutionary; so, he is a Russian who came to America in exile after the revolution, just like Nabokov.

Leningradus is both an allusion to Lenin and the city of Leningrad.

Commentary to line 172 (books and people):

“Speaking of the Head of the bloated Russian Department, Prof. Pnin, a regular martinet in regard to his underlings (happily, Prof. Botkin, who taught in another department, was not subordinated to that grotesque perfectionist).”

Pnin is, of course, the professor from Nabokov’s eponymous novel. Why does Kinbote mention that “happily”, Botkin is not subordinated to Pnin? Because they are the same person - and Kinbote sometimes slips, letting the real Botkin show.

Line 189: Starover Blue

A fun little wordplay. Star Over Blue, as well as Starover - this was a kind of Christian denomination in Imperial Russia. The comment sends the reader onto a chase:

“See note to line the 627. This reminds one of the Royal Game of the Goose, but played here with little airplanes of painted tin: a wild goose game, rather (go to square 209).”

What happens if we follow these instructions?

Turning to line 627:

We are given a small biography of Prof. Blue; we are told of a Sinyavin who “migrated from Saratov to Seattle and begot a son who eventually changed his name to Blue and married Stella Lazurchik” (lazurniy means azure in Russian). I think I’m missing something.

Turning to line 209:

We are given a brief description of Gradus flying.

Filling in the blanks for the commentary to line 231:

“Poor old man Swift, poor -, poor Baudelaire”

Swift and Baudelaire both went insane. Putting Botkin into the blank fits the meter.

In the comment to line 286:

“Even in Arcady am I, says Death in the tombal scripture.”

This is a reference to a painting: Et in Arcadia Ego. Analysis of the painting lets a careful viewer see the message: even in the idyllic fields of Arcadia, Death is always looming. It’s interesting to note that throughout the book, New Wye is often described by Kinbote as “Arcadia”. Could this be alluding to the fact that Kinbote, Gradus and Botkin are all made up? If Kinbote refers to Death as “I”, perhaps the alter egos of Gradus and Kinbote are getting mixed up.

In the same commentary we meet a character called Ferz Bretwit; ‘ferz’ is the Russian name of the queen piece in chess. I think there is another chess composition line here - maybe related to the Jewels? - but I need to read this more carefully to check.

Commentary to lines 347-348:

“But then it is also true that Hazel Shade resembled me in certain respects.”

Are they both suicidal?

Commentary to lines 376-377:

“Netochka as we called the dear man…the gentleman will be less worried about the fate of my friend’s poem after reading the passage commented here. Southey like a roasted rat for supper - which is especially comic in view of the rats that devoured his Bishop.”

Kinbote again betrays his true leaning, calling Nattochdag (Night or Day?) as Netochka, the Russian diminutive abbreviation.

Southey was known to be an eccentric poet; this passage is in reference to one of his poems, God’s Judgement on a Wicked Bishop:

Down on his knees the Bishop fell,

And faster and faster his beads did he tell,

As louder and louder drawing near

The gnawing of their teeth he could hear.

And in at the windows and in at the door,

And through the walls helter-skelter they pour,

And down from the ceiling and up through the floor,

From the right and the left, from behind and before,

From within and without, from above and below,

And all at once to the Bishop they go.

They have whetted their teeth against the stones,

And now they pick the Bishop's bones:

They gnaw'd the flesh from every limb,

For they were sent to do judgment on him!

Is this also part of the chess puzzle? I’m not sure. Need to check again after.

Commentary to lines 433-434:

We are introduced to the character of “Lavender”. Lord Byron was also, for a short time, taken care of by a man named “Lavender”.

Commentary to lines 493:

Kinbote extensively discusses suicide:

“There are purists who maintain that a gentleman should use a brace of pistols, one for each temple, or a bare botkin…or drown with clumsy Ophelia...The ideal drop is from an aircraft, your muscles relaxed, your pilot puzzled, your packed parachute shuffled off, cast off, shrugged off - farewell, shootka (little chute!)”

Hazel Shade drowned like Ophelia; Kinbote considers suicide once mentioning the work ‘botkin’; shootka means ‘joke’ in Russian. Note that the next commentary is one which I previously spoke about, concerning yew trees and suicide.

Commentary to line 549:

Kinbote gives a fake Augustine quote. Trying to impress Shade?

Commentary to line 579:

“Initiation took place on Saturday, March the 14th…”

March 14th is the night before the Ides of March. I’m not sure if this has any meaning or is a coincidence.

Commentary to line 629:

Another reference to Arcadia.

Commentary to lines 671-672:

This is a reference to Browning’s poem, My Last Duchess:

“Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!”

After researching this, it’s clear that Browning’s poem is about a deranged man, whose memory of abuse towards a previous wife is misconstrued in his memory as completely normal.

Commentary to line 741:

“What stunning conjuring tricks our magical mechanical age plays with old mother space and old Father Time!”

Kinbote (Gradus?) quote Shade.

“He was a merry, perhaps over merry, fellow in a green velvet jacket. Nobody liked him, but he certainly had a keen mind. His name, Izumrudov, sounded rather Russian but actually meant ‘of the Umruds’, an Eskimo tribe sometimes seen paddling their umyaks (hide-lined boats) on the emerald waters of our norther shores…the gay green vision withdrew - to resume his whoring no doubt. How one hates such men!”

Izumrud is the Russian word for emerald. Note that Kinbote is particularly dislikable towards another member of the university faculty, Gerald Emerald, who makes fun of Kinbote. Does this show that Kinbote’s invention of characters stems from a characterisation of real-life people who make fun of him, e.g. Emerald? Botkin turns his real-life enemies into Zemblan villains.

It’s also worth noting that in a previous passage, a man in a “bottle-green jacket” is seen lounging around with a prostitute. I assume this is the same person.

I still have a lot more to add to this, and I’ll continue updating this document as I find more stuff. I have also discovered a lot of nice leads in the Index.